Dec 31, 2025

Business strategy is about value creation through distinction

A business unit’s strategy describes how the unit uses business processes to position the unit’s customer-perceived value propositions to well suit customer needs, all with relatively low competition and costs. The holder of such a strategy is said to possess a competitive advantage, either by differentiation (targeting relatively lightly-competed market segments) or low costs[i]. A strategy that creates a competitive advantage will create value (in excess of peers) as recorded by economically sound metrics. This value it will always create by either commanding premium product prices, improving cost-effectiveness (including investment costs), or creating revenue growth, other things being equal – or by a combination of these[ii] – no matter what strategic logic, business model, or deployment of digital technology it is based on.

For example, a very successful platform business – which typically has much relative scale – is very valuable for the reasons that it commands premium prices even if it is not a veritable monopoly, having successfully differentiated itself as a very good or the best product, and enjoys a cost advantage due to economies of scale[iii]. An example of both advantages is the advertising products that Amazon Marketplace offers companies. Marketplace is a platform business of Amazon involving market “sides” such as non-Amazon product sellers, advertisers, and consumers.

Strategic positioning in market segments and by differentiation or cost advantage occurs in the context of industry structure. Industry structure is how companies, their relationships, and the market as a whole are organized, including factors such as trends in company sizes and market concentration toward oligopoly (a few companies only), conditions of entry to and exit from the industry.

Generally, any industry structure importantly tells about the intensity and other structural characteristics of competition, revealing information about whether and how companies could make above-par profits with respect to those active in the “average industry,” and guiding strategy formulation, such as entry and exit decisions and positioning. Structure can also – and always should – be given consideration on the market segment level.

Industry structure is usefully depicted in a model of five “competitive forces.” The forces jointly determine the essence of industry structure for strategists, describing how much market power (to retain parts of margin for themselves) those competing for your profits hold: customers, suppliers, and three competitor classes: current ones, prospective new market entrants, and sellers of substitute products[iv]. Some augment this framework with a sixth force that differs in that its presence improves your market power: the power of complementary-product sellers[v].

For longer-term value creation, strategy typically needs to be backed up by difficult-to-reproduce resources that enable business processes to produce a valuable strategic position well[vi] – resources like a high-quality AI-use capability for content production or an operational-excellence capability for lowering manufacturing costs. Moreover, a company usually needs to have pursued advantages in a selected set of market segments[vii], each targeted with a tailored value proposition, since the alternative of targeting an entire mass market is rarely a successful choice even for large companies. Sustainability of a competitive advantage relies, in this classic view, on isolating mechanisms that make the imitation of distinctive positions or resources uncertain, costly, or ineffective[viii].

Such classic strategy continues to be very well suited to many of the numerous industries that the broad business sectors divide into. Yet, companies in other industries need to focus on understanding strategic opportunities and needs via the frameworks of what I call modern strategy – lenses of the strategist that allow understanding such dynamic circumstances, and often relate to what new digital technology makes possible.

Adaptive strategy: transient advantages for dynamic business environments

Some industries and market environments involve so quickly and frequently shifting customer needs that uncertainty about what is needed next is high compared with how swiftly product development cycles can be made to work. Change in such dynamic markets can be nonlinear, industry structures and market boundaries blurred, and market participants ambiguous and themselves changing[ix]. Such uncertainty can be caused by rapidly changing technology, such as the currently-topical shifts in generative AI’s capabilities, changing regulations, or other changing factors that are hard to predict early. Such changes will sometimes also make feasible a new business model – a valuable configuration of processes (value-creating activities or sets of them) that appears qualitatively distinct from others[x].

In situations like that, it is hard or impossible to sustain a single competitive advantage for even a medium term[xi], unless the market “tips” toward a virtual monopoly by the first or a near-first mover, as in cases with strong network effects (geometric benefits from extra users joining the ecosystem)[xii]. Maintaining so-called dynamic capabilities[xiii], such as market “vigilance”[xiv] or an agile product development capability[xv], can nonetheless enable some companies to enjoy competitive advantages for a longer term. This is due to these capabilities’ ability to buttress a strategy that quickly adapts to fast-moving customer needs. Also, a set of partially-developed and partially-paid paths to succeeding in a new circumstance – real options – can help to respond rapidly[xvi]. A company with such a modern, adaptive strategy[xvii] has achieved strategic flexibility[xviii] while still having a purposeful strategy – something that all companies certainly should have.

How strategy ties together all competitively important aspects of business

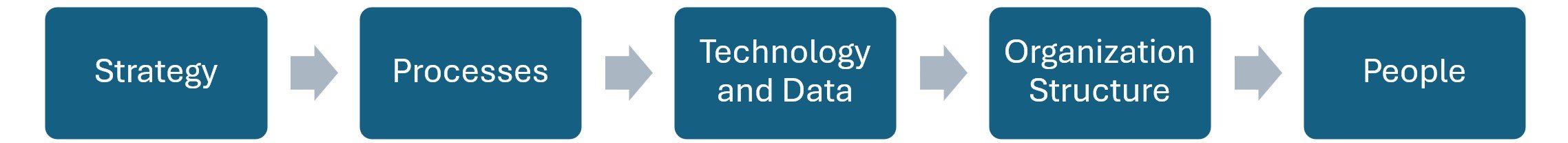

The basic elements of how a business is run – its strategy, processes, and technology, among others, should "fit" together synergistically[xix]. Ideally, a carefully-formulated strategy should first determine another element, then that element yet another element, by and large in a specific order as depicted below.

For example, the need for a strategy alignment of a company’s information technology is an old adage for business IT experts.[xx] Also organizational structure should be clearly derived from strategy[xxi], and in some of its broadest lines, it tends to be[xxii]. Business processes, IT, organization structure, and the talent residing in people, have various mutual synergies, if organized in specific ways depending on the needs of business.[xxiii] The figure shows how processes, technology and data, and organization structure “mediate” the entire progression from strategy to the people that occupy the organization. Worth a mention is that value capabilities (or, strategic or distinctive capabilities) themselves are clusters of various components from the image; e.g., their knowledge element includes employee skills and managerial systems, among others. That is to say, powerful capabilities exhibit fairly much of internal fit[xxiv].

A company should, by default, aim to have all these parts support achieving competitive advantage, with appropriate focus.

Neither that fast-moving business environments require more strategic flexibility, nor that small companies – or indeed any company – can’t tailor processes too far, are exceptions to the rule but rather a manifestation of it: “appropriate focus” takes various circumstances into account. This includes prioritization of which synergies to design for, and how deeply to “commit” to a strategy by building elaborate, fine-tuned designs instead of retaining flexibility[xxv]. Achieving relative “fit” can importantly support both reaching and sustaining competitive advantages certainly for most companies[xxvi], assuming a competent design and a competent change management process.

In practice, therefore, such sufficient fit does not imply an elaborate and unfeasible “management science” optimization of a system as if it were a machine in a laboratory. Nonetheless, fit remains an underutilized source of sustaining a competitive advantage.

Strategists benefit from an eclectic understanding of business practice

Strategic concepts can “tie together” an entire business in other ways, too. For example, one often hears talk of substrategies involving a certain part of the business. Here, the key is to understand that a substrategy should describe the role of some component of a business unit’s work in fulfilling the business (entire) strategy. For example, technology strategy describes technology’s role in business strategy[xxvii], and, as one of its components, an AI strategy describes the role of AI in business strategy – as reflected in the figure above, again.

These characteristics of high-quality strategies, including the role of multi-function business processes in creating and capturing the value that strategy enables, illustrate how best strategists usually understand business eclectically and holistically, having knowledge such as a relatively deep understanding of several core and other business functions, of industry structures and lifecycle phases, and of the business impacts of new technology. As part of that, a particularly important aspect of strategy formulation is to create capabilities to sense and understand evolving customer needs (customer value, that is)[xxviii] and in which ways can the company’s base of resources be a match with a strategic market position.

Furthermore, some strategists adopt the lens of game theory to prepare moves and responses to countermoves of competitors in an oligopoly market[xxix]. Such a game plan is one alternative definition for the term dynamic strategy[xxx] (not to be confused with adaptive strategy, a competing though conceptually related definition for the term). Game theory must rely on numerous assumptions, tending to be too stylized (simplified) for valuable real-life applications.

Strategy, strategic management, and this blog

As mentioned, strategy is about above-par success. This term is a synonym for value creation, given that new economic value includes only value in excess of the business’ cost of capital[xxxi]. The study of strategy is the only business school subject that provides a holistic explanation of why and how some businesses bring competition-beating results while others do not.

This blog deals with strategy and the role of technology in achieving competitive advantages. With respect to strategy, the blog focuses on the content of strategy and not its creation or effectuation processes, though understanding a strategy’s ongoing execution processes – that is, ongoing value-creating business processes when a new strategy is up and running – is part of strategy, as explained.

Strategic management is a broader term than strategy and includes the strategy formulation process – or in short, the strategy process – and will, in some definitions, also involve the process of effectuating a new strategy.

Dec 31, 2025

Notes

[i] See Michael E. Porter, Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors (New York: Free Press, 1980), Chapter 2.

[ii] A strategy could create value also be mitigating (business) risks to lower the cost of capital, but companies usually have much better chances of strategic value creation when done via improved profitability or growth. However, changes that improve operational effectiveness and can be quickly imitated by competitors can’t noticeably create value (above-par business success), as they can’t sustain a competitive advantage for a significant time. Reducing the cost of capital via basic financial management (as opposed to strategic business management), such as by an optimized capital structure, is an example of operational effectiveness. Changes improving operational effectiveness are not a strategy or part of one. See Michel E. Porter, What is strategy? Harvard Business Review (Nov-Dec 1996), 61–78.

[iii] Some platform businesses’ ability to achieve both simultaneously is typically due to the support that network effects – an important strategic phenomenon – lend to both differentiated value and cost reduction. These advantages mostly come through the increasing returns to scale, externalized-to-an-ecosystem (quick, cheap, and low-risk) development of interactions or products. For Van Alstyne et al., this “inverts the firm” to produce modular variety in potential interactions or products, many complements to each other. Moreover, as software is central to digital platforms, software’s fixed-cost-heavy cost structure further enables scale economies, and automated personalization drives further differentiation advantages. The ability to combine both competitive advantage types counters the omission of network effects as a major entry barrier and also counters the so-called stuck-in-the-middle thesis by Porter, Competitive Strategy, 7-17, 41-44. Marshall W. Van Alstyne, Geoffrey G. Parker, and Sangeet Paul Choudary, Pipelines, platforms, and the new rules of strategy, Harvard Business Review 94(4), 2016: 54-62. See also David P. McIntyre and Arati Srinivasan, Networks, platforms, and strategy: Emerging views and next steps, Strategic Management Journal 38(1), 2017: 141-160.

[iv] Porter, Competitive Strategy, Chapter 1.

[v] Adam M. Brandenburger and Barry J. Nalebuff, Co-opetition, New York, Doubleday Business, 1996.

[vi] Birger Wernerfelt, A resource‐based view of the firm, Strategic Management Journal 5(2), 1984: 171-180; Jay Barney, Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage, Journal of Management 17(1), 1991: 99-120.

[vii] Michael E. Porter, Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance (New York: Free Press, 1985), Chapter 7; Wayne S. DeSarbo, Kamel Jedidi, and Indrajit Sinha, Customer value analysis in a heterogeneous market, Strategic Management Journal 22(9), 2001: 845-857.

[viii] Richard P. Rumelt, Towards a strategic theory of the firm, in Robert Boyden Lamb (ed.), Competitive Strategic Management (Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1984): 556-570.

[ix] Kathleen M. Eisenhardt and Jeffrey A. Martin, Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strategic Management Journal 21(10/11), 2000: 1105-1121.

[x] See Raphael Amit and Christoph Zott, Business Model Innovation Strategy: Transformational Concepts and Tools for Entrepreneurial Leaders (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 2020).

[xi] Richard A. D’Aveni, Hypercompetition: Managing the Dynamics of Strategic Maneuvering, New York: Free Press, 1994.

[xii] Michael L. Katz and Carl Shapiro, Network externalities, competition, and compatibility, American Economic Review 75(3), 1985: 424-440; a variation of these viewpoints is elaborated by Joseph Farrell and Garth Saloner, Installed base and compatibility: Innovation, product preannouncements, and predation, American Economic Review, 76(5), 1986: 940-955.

[xiii] David J. Teece, Gary Pisano, and Amy Shuen, Dynamic capabilities and strategic management, Strategic Management Journal 18(7), 1997: 509-533.

[xiv] George S. Day and Paul J. H. Schoemaker, See Sooner, Act Faster: How Vigilant Leaders Thrive in an Era of Digital Turbulence. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2019.

[xv] Some of the early insights about agile product development – not using that title – by management scholars were given by Kathleen M. Eisenhardt and Behnam N. Tabrizi, Accelerating adaptive processes: Product innovation in the global computer industry, Administrative Science Quarterly 40, 1995: 84-110.

[xvi] Lenos Trigeorgis and Jeffrey J. Reuer, Real options theory in strategic management, Strategic Management Journal 38(1), 2017: 42-63; T. A. Luehrman, Strategy as a portfolio of real options, Harvard Business Review (Sep-Oct 1998, 89–99); Nalin Kulatilaka and Enrico C. Perotti, Strategic growth options, Management Science 44(8), 1998: 1021-1031; Nalin Kulatilaka and Stephen Gary Marks, The strategic value of flexibility: reducing the ability to compromise, American Economic Review 78(3), 1988: 574-580.

[xvii] See Eric L. Chen, Riitta Katila, Rory McDonald, and Kathleen M. Eisenhardt, Life in the fast lane: Origins of competitive interaction in new vs. established markets, Strategic Management Journal 31(13), 2010, 1527-1547; Yves Doz and Mikko Kosonen, Fast Strategy: How Strategic Agility Will Help You Stay Ahead of the Game, Harlow, UK, Wharton School Publishing, 2008; Eisenhardt and Tabrizi, Accelerating adaptive processes.

[xviii] See Sucheta Nadkarni and Vadake K. Narayanan, Strategic schemas, strategic flexibility, and firm performance: The moderating role of industry clockspeed, Strategic Management Journal 28(3), 2007: 243-270.

[xix] Porter, What is strategy?; Michael E. Porter and Nicolaj Siggelkow, Contextuality within activity systems and sustainability of competitive advantage, Academy of Management Perspectives 22(2), 2008: 34-56.

[xx] Anandhi Bharadwaj, Omar A. El Sawy, Paul A. Pavlou, and N. Venkatraman, Digital business strategy: Toward a next generation of insights, MIS Quarterly 37(2), 2013: 471-482.

[xxi] This is often much due to how information can be efficiently transmitted for effective transactions, as outlined by Oliver E. Williamson, The vertical integration of production: Market failure considerations, American Economic Review (Papers and Proceedings) 61(2), 1971: 112-123.

[xxii] Alfred D. Chandler, Jr., Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the American Industrial Enterprise, Cambridge, MA, MIT Press, 1962.

[xxiii] IT-organization synergies are discussed by Timothy F. Bresnahan, Erik Brynjolfsson, and Lorin M. Hitt, Information technology, workplace organization, and the demand for skilled labor: Firm-level evidence, Quarterly Journal of Economics 117(1), 2002: 339-376.

[xxiv] Dorothy Leonard‐Barton, Core capabilities and core rigidities: A paradox in managing new product development, Strategic Management Journal 13(S1), 1992: 111-125.

[xxv] See Jörg Claussen, Tobias Kretschmer, and Nils Stieglitz, Vertical scope, turbulence, and the benefits of commitment and flexibility, Management Science 61.4 (2015): 915-929.

[xxvi] Porter and Siggelkow, Contextuality within activity systems.

[xxvii] Michael E. Porter, 1983, The technological dimension of competitive strategy, in Richard S. Rosenbloom (ed.), Research on Technological Innovation, Management, and Policy 1 (Greenwich, Connecticut: JAI Press: 1-33).

[xxviii] George S. Day and Christine Moorman, Strategy from the Outside In: Profiting from Customer Value (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2010).

[xxix] See Pankaj Ghemawat, Games Businesses Play: Cases and Models (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1997).

[xxx] Trigeorgis and Reuer, Real options theory.

[xxxi] Naturally, the objective of business to create value is guardrailed by numerous constraints, such as laws and business ethics, including sustainability issues.